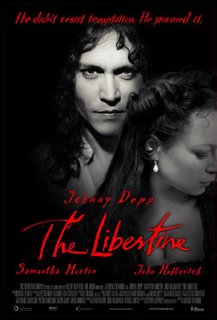

Johnny Depp is The Libertine

“Allow me to be frank: you will not like me,” a foppishly dressed Johnny Depp growls directly into the camera. So ends the trailer for his latest picture, The Libertine. After starring in two straight movies which were widely enjoyed by the public (Finding Neverland and Pirates of the Caribbean), Depp is now making a biopic of John Wilmot, the second Earl of Rochester. (Ever known for his controversial roles, Depp may be anxious that his pending two-sequel deal on Pirates could, horror of horrors, brand him as a popularly beloved actor.) The Libertine, an art-house project also starring John Malkovich as Charles II, recounts Wilmot’s debauched and treacherous life, and promises to paint the licentious Earl as the consummate anti-hero of the Restoration court.

“Allow me to be frank: you will not like me,” a foppishly dressed Johnny Depp growls directly into the camera. So ends the trailer for his latest picture, The Libertine. After starring in two straight movies which were widely enjoyed by the public (Finding Neverland and Pirates of the Caribbean), Depp is now making a biopic of John Wilmot, the second Earl of Rochester. (Ever known for his controversial roles, Depp may be anxious that his pending two-sequel deal on Pirates could, horror of horrors, brand him as a popularly beloved actor.) The Libertine, an art-house project also starring John Malkovich as Charles II, recounts Wilmot’s debauched and treacherous life, and promises to paint the licentious Earl as the consummate anti-hero of the Restoration court.The film is being marketed as “the most controversial movie of the year”—controversy, of course, being the only way such a movie ever makes money. However, if it lives up to the trailer’s glimpses of sex, lies, and violence, it will simply be yet another film cut from contemporary Hollywood’s cloth. A Tinseltown movie featuring a rogue who shocks his peers with liberal views on sex?! How scandalous! How original! (Competition note: Touchstone Pictures presents their paean to Casanova just weeks after The Libertine is released.)

However, there is an element in Rochester’s story that could yield a truly controversial film. In popular British culture of old, John Wilmot was indeed legendary—but not as the foppish gent who, as the movie will highlight, wrote a pornographic play lampooning the king who commissioned it. Instead, Wilmot was renowned as one of England’s most famous deathbed converts to the Christian faith. Should this art-house flick boldly depict Wilmot’s ultimate redemption, should it illustrate the staggering ability of God’s grace to reach even the most desperate sinner—should it show us how a libertine once found true liberty—it may well prove to be the year’s most controversial film.

But my hopes aren’t high. Johnny Depp has already predicted it: I probably won’t like the Libertine.